Wheels In — Intro and Opening Thoughts

Last week, we kicked off our three-part series on the Pillars of Innovation in MSK VBC with Pillar #1, Value-Based Payment models. This week, we cover Pillar #2, Care Migration to the ASC. “Site of service” is a hot topic in healthcare reform. Hospitals and health systems have long benefited from facility fees—additional charges for tests and procedures performed on their campuses. Site-neutral payments (and the battle over them) will be covered in a future post. Meanwhile, the shift of care to outpatient settings, including ASCs, is well underway and expected to continue. McKinsey covered this shift in great detail, estimating that ambulatory care will grow to 32% of total healthcare activity by 2030. MSK care arguably represents the biggest opportunity to achieve value through shifting site of service.

With that, we present Pillars of Innovation Part 2: Care Migration to the ASC.

Dem Dry Bones

From the EIC’s Desk

Pillar #2 — Care Migration to the ASC

The second pillar of musculoskeletal care innovation is the migration of procedures to the outpatient setting, specifically ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs). Ambulatory orthopedic surgeries, like carpal tunnel release and shoulder arthroscopy, are not new. What is new—and exciting—is the transition of higher acuity MSK procedures like joint replacements and spine surgeries to ASCs. When I started my career 15 years ago, the idea of sending a hip or knee replacement patient home the same day seemed outlandish. Patients remained in the hospital for three days or more following surgery, with many discharged to expensive rehab centers. A joint replacement surgeon in an ASC was like a fish out of water. Times have changed.

Nowadays, hip and knee replacement patients are discharged home 2-3 hours after their procedure. Some surgeons even perform straightforward revision joint replacement surgeries in an ASC, a concept unthinkable a few years ago. Spine procedures have seen a similar shift to the outpatient setting. One- to two-level cervical and lumbar fusions, laminectomies, discectomies, and even more complex interbody fusion surgeries are all being performed safely in ASCs.

Several factors have facilitated the migration of higher acuity MSK cases to surgery centers. Preoperative screening and optimization protocols allow for identification of patients appropriate for same-day surgeries. Improved surgical and anesthetic techniques facilitate rapid mobilization of patients and direct discharge home. By removing joint replacement procedures from the inpatient only list, CMS paved the way for outpatient joint replacements. During the pandemic, closure of hospital operating rooms meant inpatient spine and joint surgeries weren’t possible. Patients and surgeons embraced ASCs out of necessity.

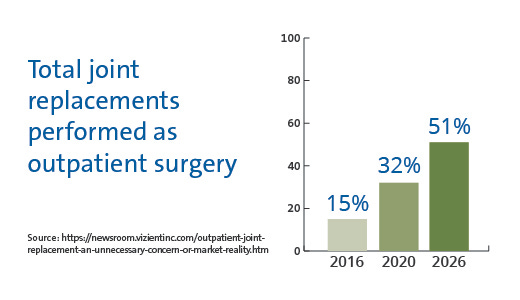

There is ample evidence to support the safety of performing these procedures in ASCs. One study demonstrated a 98% rate of discharge home, with one planned discharge to a rehab facility (the other 2%). There were no major adverse events in the 90-day postoperative period using advanced anesthesia techniques and strict selection criteria. I suspect selection criteria will become (safely) more liberal, resulting in an even greater number of spine and joint procedures taking place in ASCs. Exact estimates vary, but expectations are that at least 50% of these cases will be performed in ASCs by 2030 (and that estimate may be conservative).

How does migration of MSK cases to ASCs support value-based care? Simply put, ASCs cost less—significantly less. With their low overhead, efficient processes, and alignment of incentives, ASCs provide a similar (or higher) level of care than inpatient or hospital outpatient settings at lower expense. It’s estimated that shifting 50% of joint replacement surgeries to ASCs could save commercial payers and employers $2 billion per year and CMS $1 billion per year. Not surprisingly, it’s difficult to pin down the cost of joint replacement surgery in a hospital. Prices vary widely from one facility or geography to the next.

Blue Cross Blue Shield conducted a claims data study a decade ago to analyze cost variations for hip and knee replacement surgeries in the U.S. The findings are revealing: a knee replacement costs more than $60,000 in New York City, compared to an average of just $16,000 in Montgomery, Alabama, a nearly fourfold difference. Regional disparities were expected, but the study also uncovered significant cost variations within the same geographic areas, with variances reaching 267% in Dallas and 185% in Boston. The relationship between cost and quality is intricate, as higher prices often reflect stronger bargaining power rather than superior quality.

ASCs contribute to the VBC MSK equation by providing high-quality, cost-effective care focused on patient experience. Average costs for ambulatory TJAs are 40% lower ($11,677 vs. $19,361). In appropriately selected patients, outpatient joint replacement in an ASC yields low rates of complications, readmissions, reoperations, revisions, and ED visits, comparable to the hospital outpatient setting. Finally, outpatient joint replacement achieves high patient satisfaction scores, exceeding those of inpatient procedures. Outpatient MSK procedures in the ASC setting define value-based care.

My first outpatient joint replacement was not planned. It was a routine hip replacement in a generally healthy patient who declined hospitalization. Outpatient joint replacement was not widely practiced at the time. I was aware of forward-thinking centers performing outpatient joint replacements routinely (and literature demonstrating it was safe). The patient walked with PT and was deemed safe for discharge. We sent him home, and he did well.

Six years ago, I became a part owner in an MSK-focused ASC. My first planned outpatient hip replacement was both exciting and nerve-wracking. By that time, most of my inpatient joint replacement patients were discharged within 24 hours, and I had performed several outpatient cases in the hospital. I was prepared. The case went smoothly, and the patient walked out of the facility on crutches just a couple of hours after recovery. Today, outpatient joint replacements in the ASC are routine. Our ASC achieves unprecedented Press Ganey scores, and patients praise the experience. I have a reliable staff, a level of autonomy and control, and an incentive to deliver high-quality, cost-effective care as a part owner. By performing joint replacements in the ASC, I can save the system tens of thousands of dollars per procedure.

Most expect the trend toward ASC joint and spine procedures to continue. In future articles in this series, we’ll dive into the future of MSK in the ASC, including facility-based bundled payments, decentralized centers of excellence, and the micro-hospital concept.

- Ben

Small Incisions

Quick Takes on Timely Topics

Stop letting MA plans deny care using AI tools, lawmakers urge CMS (StatNews)

AI’s ability to improve efficiency and workflow in health care back-office functions is a double-edged sword. While it’s great that these tools can improve clinical workflows, it’s not so great that they can be used to rapidly deny care. Beyond application as a slightly less blunt instrument of prior authorization and utilization management, questions remain about how AI/ML should and can be used in medicine.

Practicing outside of the health care mecca that is Boston, I empathize with Summa Health’s position in the shadow of a well-known health care giant. Some patients will always gravitate to brand-name health care. However, it is possible to compete with these entities by delivering high-quality, high-touch, personalized care. You can carve out a niche by being nimble and cutting-edge in a way massive health systems can’t—in essence, zigging while they continue to zag.

Oshi Health: Insights to Scale a Specialty Care Model (On the Flying Bridge)

Oshi Health, focusing on gastroenterology, is an innovative specialty care model success story. The principles laid out here align well with concepts we’ve been discussing in “The Surgeon’s Record.” These include the size of market matters, team matters, more need for outcomes data, the novelty of VBC models, balancing supply and demand, the tech-forward approach, capital intensity, and virtuous cycles. The last principle, creating a virtuous cycle, is the inflection point of scalable specialty care.

The biggest trends challenging physicians (Medical Economics)

Not surprisingly, administrative work was cited most frequently. What may be surprising is that 66% of physicians are not using AI in their practices. Many physicians may be using AI (directly or indirectly) and simply aren’t aware of it. “Artificial intelligence” is a broad term that encompasses a wide array of technological applications. As these tools become more commonplace, it’s important to be explicit as to where and how they’re being used. Of equal importance is raising clinician comfort level and awareness.

The Gold Standard

Polling the Crowd

The Light Box

Health Care Visuals

From the Gallery

Amplifying Community Voices

This episode of the excellent “43cc” podcast, hosted by Drs. Wendy Dean and Matt Ramsey, had me chuckling, smiling, reminiscing, grimacing, and sighing all in the span of 45 minutes. Most of all, it left me convinced that there is an audience and need for what we’re trying to achieve here with “The Surgeon’s Record.” The July 4th episode (“Is there a Dr. in Charge?”) is a no holds barred look into the psyche of physicians. It should be required listening for anyone building in health care.

Wheels Out — Signing Off and Looking Ahead

Pillar #1 (value-based payment models) and Pillar #2 (migration to ASCs) form a solid foundation of specialty care innovation. While these concepts are particularly important in MSK VBC, they can be easily applied to other types of care such as cardiac and GI. Both pillars have existed for some time, but we haven’t quite figured out how to successfully tie them together to make VBC a sustainable reality. What’s missing is a catalyst and adhesive capable of making the sum of these principles greater than their respective parts. That critical element is Pillar #3: Implementation of Technology—the topic of next week’s post and the final in this series.

See you then,

Ben Schwartz, MD, MBA

Editor-in-chief/Senior Clinical Fellow