One to Zero

What Silicon Valley Gets Wrong about Trust in Healthcare

This tweet popped up on my feed this past weekend (h/t to Blake Madden, who called it out). The slide in question is based on findings from a JAMA Network Open Access study published in July. I found Marc Andreessen’s tweet concerning for several reasons and initially posted my thoughts on LinkedIn. The post generated a lot of interest and led to a great discussion. Topics like physician trust, AI replacing doctors, and Silicon Valley VC views of health care resonate with many. I’ve thought more about the tweet and its implications for health tech, the study itself, and the concept of physician trust. For this week’s post, I wanted to add more depth and nuance to the discussion while taking a deeper dive into the issue of trust in healthcare.

Thanks to all who commented on the post and shared their thoughts — let’s keep the discussion going.

The Tweet

First, as many pointed out, Andreessen’s interpretation of the slide is incorrect. Trust in physicians and hospitals isn’t down to 31.4%; it dropped 31.4% during the study period. Certainly not something to celebrate. But as we’ll discuss later, misinformation is a key contributor to loss of trust. Lack of context and misrepresentation aside, it’s disappointing that Andreessen, a well-known VC with a powerful firm and large following, would take such apparent joy in his dire prediction.

Lack of trust in traditional health care providers is problematic for multiple reasons. It opens the door even wider for misinformation and any number of opportunistic grifters (happy to tell people what they want to hear, for the right price). Sowing distrust for self-serving reasons is not unique to health care. But when it comes to a person’s health and well-being, the results can be disastrous. The complete erosion of the doctor-patient relationship would certainly lead to greater health care costs and worse outcomes. Distrust in the medical system leads to underutilization of services, poor adherence to treatment, worse self-reported health status, and less preventive care.

The purpose of Andreessen’s tweet is probably to pump up his own book. His firm, Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), is betting big on AI and hasn’t been shy about extolling its virtues in health care. Silicon Valley VCs seem particularly enamored by the potential of AI to replace doctors. Vinod Khosla has made similar comments. “Doctors don't scale" is a common argument. Investors would love to figure out how to SaaS health care to get tech-like returns. To date, few of those efforts have been successful — financially or clinically.

AI is seen as a potential solution to the scale problem — easy-to-disseminate algorithms performing at or above the level of clinicians. I’m bullish on AI in health care. To deny its potential is foolish and protectionist. We’re entering a future where AI makes us better at our jobs. However, this fixation on using AI to replace doctors is misguided.

Medicine is about more than making a diagnosis. The doctor-patient relationship is complex. Some of the biggest issues we face can’t simply be solved by tech. Opinions like Marc Andreessen's indicate a level of ignorance about how health care works. This is why I advocate for spending time in a clinical setting. I guarantee your perception will change. (As always, I extend an open invitation to anyone to come experience health care on the frontlines.)

While you can't scale doctors the way Silicon Valley VCs want, you can scale care models. You can aggregate high-quality physicians and create high-performing networks of cost-efficient outpatient centers. Technology undoubtedly has a role to play in advanced care delivery. There’s no need to spread half-truths or tear down traditional medicine to usher in an era of tech-enabled care. Building advanced models may not get tech unicorn-level returns, but it’s more likely to be successful than trying to SaaS health care.

(Side note: I’m curious how physicians who work for a16z or portcos founded by doctors feel about this tweet).

The Study

The study in question explores how trust in health care providers — specifically physicians and hospitals — shifted over the course of the pandemic. Conducted through a large internet survey involving over 443,000 U.S. adults, the study tracked responses across 24 waves from early 2020 to early 2024. Key findings include a steep decline in trust. In April 2020, more than 71% of respondents reported a high level of trust in physicians and hospitals. By January 2024, this number had dropped to a disappointing 40%.

Despite these stark findings, the study has limitations. It used a single question to measure trust, which may oversimplify a complex issue. Additionally, the survey combines “physicians and hospitals,” without distinguishing between the two. (To be fair, both the slide and Andreessen’s tweet reflect fact.) Since data collection occurred during the pandemic, the study findings may not be generalizable to trust in post-pandemic healthcare. The 30% decline came from the “a lot” category while the vague “some” category grew. In other words, while trust dropped, it’s hard to say by how much.

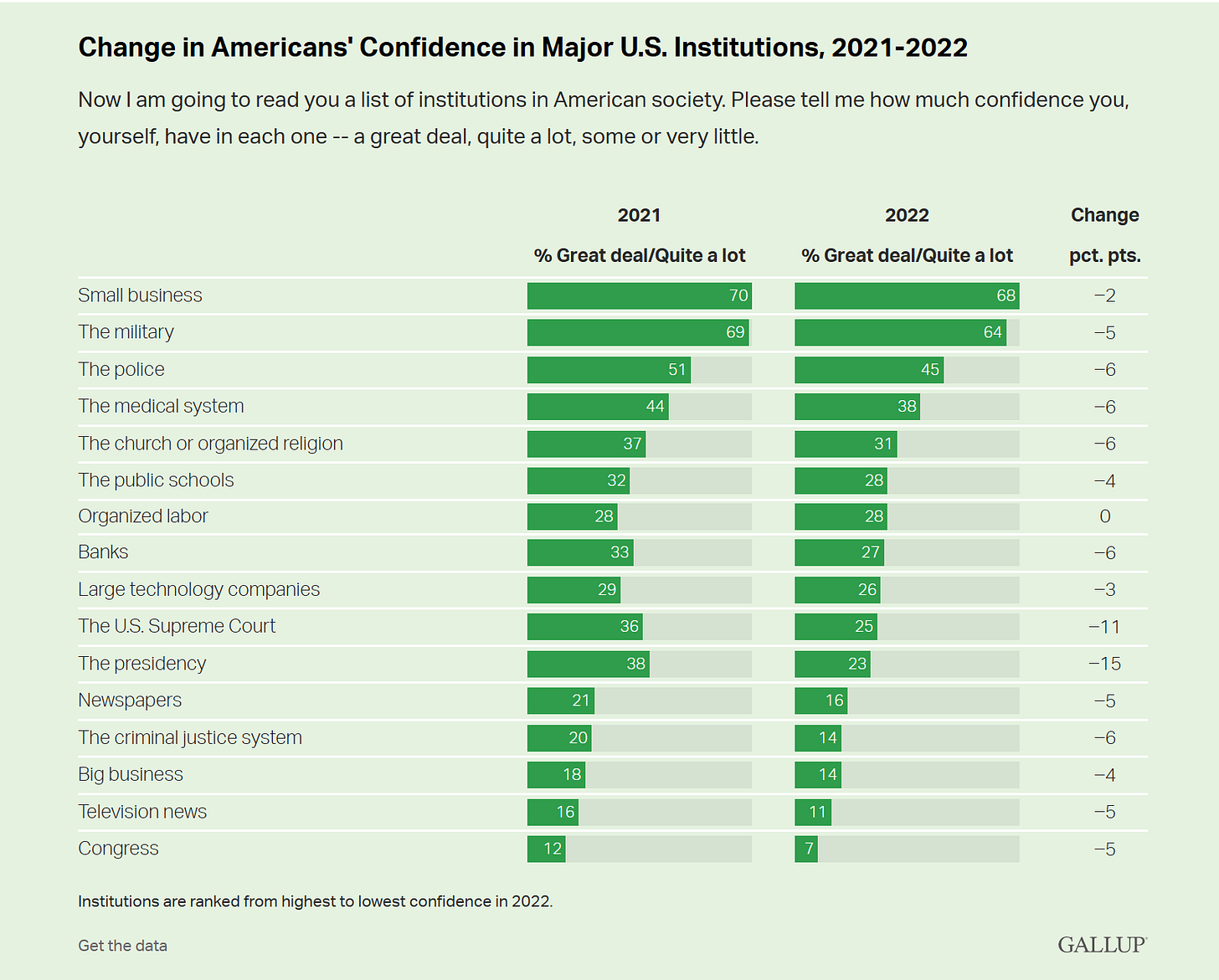

Trust in many institutions is on the decline — health care is not alone here. The reasons are multifactorial and beyond the scope of this post. Unfortunately, the pandemic was heavily politicized. It’s not surprising that patients who felt forced to get vaccinated, social distance, or wear a mask in public would lose trust in the people compelling them to do so. Debating the merits of these measures is also beyond the scope of this post. Most physicians and health systems were acting in good faith with imperfect information during an unprecedented global health event. (As I said at the time, full understanding of the pandemic will take years.)

The study specifically looked at trust during the pandemic — a once-in-a-generation black swan event. Now, almost a year from the end of the survey period, does this erosion in trust persist? A follow-up study would be necessary to answer this question accurately. Physicians and hospitals are no longer pushing social distancing, masking, and compulsory vaccination. It’s reasonable to assume that trust has at least partially recovered. Importantly, the study authors point out that “despite the observed decrease in trust in US physicians during the pandemic, aggregate levels of trust in physicians and hospitals were still substantial.”

Physician Trust

Physicians have long enjoyed a high level of trust from patients. In 1966, 73% of Americans reported having “great confidence” in medical leadership. But like other institutions, trust in health care has fallen in recent years. A recent Gallup poll demonstrated a six-point drop in respondents who have a great deal of confidence in the medical system. Measuring patient trust in physicians is difficult. Surveys, though inexpensive and easy to administer, are inherently flawed. They frequently fail to capture the complexity of the doctor-patient relationship.

It’s also difficult to separate doctors from the rest of health care when it comes to trust. Patients who don’t believe in the system still tend to like and trust their doctor. Nurses remain the most highly rated professionals for honesty and ethics — coming in at 78% in a 2023 Gallup poll (down from 85% in 2019). Over the same period, doctors fell from second place (65%) to fifth (56%), trailing nurses, veterinarians, engineers, and dentists. Other studies demonstrate more favorable results. Startup company PatientPoint released their proprietary Patient Confidence Index last month, finding that 81% of patients report trusting their doctor. However, the survey included only 2,000 patients polled over a five-day period.

Identifying the causes of mistrust is equally challenging. Health disparities, prejudices/biases, and lack of health equity are contributing factors. Medical errors and high-profile cases of malpractice erode trust even further (see Christopher Duntsch — aka “Dr. Death”). Doctors’ financial motives are being called into question. Many feel the fee-for-service “sickcare” system creates perverse incentives that drive more, not better, care. Physicians’ complicated relationship with medical industry further sows distrust. The public is constantly reminded that the U.S. has the most expensive health care system with some of the worst outcomes and lowest life expectancy rates.

The biggest contributors to mistrust? Poor communication and lack of time spent with patients. Declining reimbursement, rising overhead costs, and growing patient panels have compressed office visits. Employed physicians feel constant pressure to see more patients and generate more RVUs. Electronic health records create barriers to communication and reduce time spent listening. On average, doctors interrupt patients within 20 seconds of beginning a visit. Docs have to be encouraged to sit down to talk with a patient, something is amiss. Simply put, it’s hard to trust someone when you don’t feel heard.

A strong doctor-patient relationship is the root of trust. Value-based care has been proposed as a potential fix. By shifting focus away from volume, doctors are incentivized to achieve better outcomes by spending more time with patients. Unfortunately, VBC hasn’t yet gained enough traction to make this a reality. Ironically, AI and other tech (and the VC-backed startups offering them) can help here. Ambient scribes, RPM/RTM platforms, and patient-engagement tools free doctors to spend more time connecting with patients and less time bogged down in menial tasks. Tech should be used to build trust, not tear it down.

Patient trust is a complex issue, one that’s critical to effective care delivery. As we innovate, we must be careful not to overlook core elements of the doctor-patient relationship that define medicine. Technology and AI can be powerful tools, but they should support, not replace, humanism in care.

As we move forward, it’s crucial for health care professionals, innovators, and investors alike to prioritize trust and avoid spreading disinformation. This doesn’t mean protecting the status quo; it means finding ways to enhance what already works while respecting the nuances of medicine that technology alone can’t replicate. Rather than trying to "SaaS" healthcare, let’s aim for solutions that truly complement and elevate patient care. That’s the real opportunity.

Great post Dr. Schwartz. Physicians are going to be under enormous pressure as the financial incentives increase for startups to access patients without a desire to use doctors as an intermediary. As you said in your piece, there can be perverse incentives at play with regards to contributing to an environment of mistrust in the traditional healthcare players. Will be a major battle in our industry over the next 5-10 years.