Measuring Everything, Improving Little

How to Rescue Healthcare Quality

In US healthcare, measuring quality consumes over 100,000 staff hours and $5 million per hospital system every year, yet we’re no closer to agreeing on what quality actually means. Everyone agrees that fixing healthcare requires putting quality at the center. The harder part is defining it, measuring it, and proving that we’ve actually improved it.

Healthcare has long chased quality through an alphabet soup of programs — MIPS, BPCI, CJR, ACOs, and now TEAM and ASM. The premise of these efforts is sound: measure what matters, pay for performance (outcomes), and hold stakeholders accountable.

Results are mixed. Savings have been modest at best, especially when accounting for reconciliation payments. Outcomes aren’t any worse than traditional care, but that’s not exactly the standard we should be setting. We need to acknowledge the hidden costs of these programs, too.

Administration can be exceedingly complex with a slew of metrics and onerous reporting requirements. Preparing and reporting quality metrics comes with significant operational and financial costs. It’s hard enough for large academic centers to keep up; smaller, independent practices hardly stand a chance.

The mean per-physician cost for participating in MIPS is $12,811 per year with physicians and staff spending 201.7 hours per physician per year on MIPS-related activities. Tracking measures requires complicated registry reporting, EHR wrangling, and practice management gymnastics. In practice, quality tracking is confusing, exhausting, and expensive. There’s a whole cottage industry of third parties offering quality program management services — more hidden costs.

A big part of my role with Commons is spearheading our quality efforts — an obvious and necessary focus when you’re building a new model of specialty care. In this week’s edition of The Surgeon’s Record, we’ll discuss why these programs are so complex, what quality means for physicians and patients, and how we might start to fix things.

How We Got Here

For better or worse, quality in healthcare has largely been determined by brand, reputation, and word of mouth. As imprecise, biased, and flawed as that sounds, it’s still the way a lot of people find care.

Want to know who the best surgeons are? Ask an OR nurse. Looking for a new PCP? Head to your community Facebook forum. Those of us “in the industry” don’t go to CMS’ Care Compare website looking for quality, we get recommendations from colleagues.

Truth be told, this approach may be just as effective as any other method. But we can’t reliably measure word-of-mouth. Online ratings are notoriously poor reflections of quality and value. Greater brand reputation doesn’t guarantee higher quality (but often guarantees higher costs). We need better solutions.

Value-based care was supposed to fix this problem. Tying reimbursement to outcomes and cost-efficiency was meant to usher in an era of quality tied to financial incentives. HITECH and the ACA spawned a rogue’s gallery of acronym-laden programs, each with its own spin on the value equation.

A brief sampling:

Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) — care episode-based cost savings bundles.

Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) — a composite score tied to quality, costs, improvement activities, and interoperability.

Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM) — the newest iteration, tying hospitals and surgeons into shared accountability for procedures like joint replacement.

As a practicing surgeon, I participated in BPCI-Advanced and was highly successful in the program — saving $7,000 per joint replacement episode and $400,000 overall in the first year.

But I don’t think the program made me successful. I was simply able to capture more of the value I was already creating. We used a third party to help us administer the program, ensure compliance, and track our data. The convener was metaphorically invaluable but came with a practical cost — reduced “take home” from reconciliation payments.

In my first couple of weeks at Commons, I’ve taken a deep dive into MIPS. I have yet to come up for air. Commons is big enough now that we no longer qualify for Small Practice exemptions. There are 4 reporting categories (Quality, Promoting Interoperability, Improvement Activities, and Cost). Each category has its own fulfillment requirements, some with over 100 measures to choose from.

Patient reported outcomes measures (PROMS) are a large component of Quality but collecting and reporting them is complex and requires use of a registry. Cost is tracked by CMS, so no reporting is necessary. However, both Promoting Interoperability and Improvement Activities require attestation on CMS’ website and documentation of qualifying activities in case of audit. There’s up to a 9% penalty for failing to satisfy MIPS requirements.

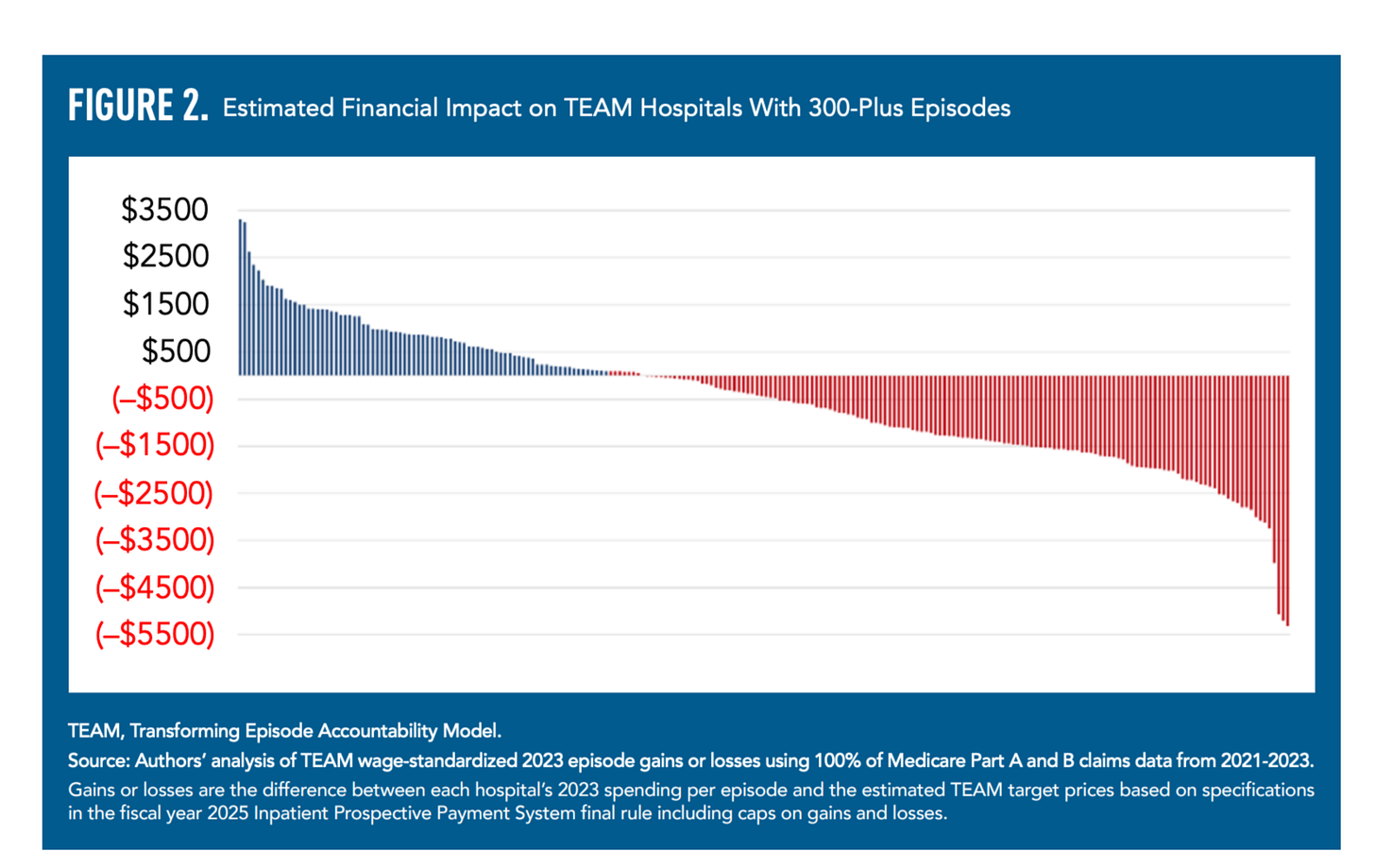

TEAM launches on January 1st, 2026, but is centered on hospitals and health systems, not physician groups like Commons. The program is coming in hot, and many hospitals aren’t ready; up to two-thirds could lose money in the program. The kicker is that TEAM is mandatory — there’s no opting out.

Is this the best way to drive quality?

The constant need to chase metrics contributes to burnout and has almost certainly contributed to the decline of independent practice. Excessive complexity, financial burden, dubious ROI, and misaligned incentives have tilted the playing field towards large systems. Too often, quality programs feel like an exercise in checking boxes or teaching to the test rather than improving care.

Demonstrating quality should be a source of pride, not a burden. So how do we do better?

A Better Way Forward

As convoluted as quality reporting is, here are some potential solutions:

1. Streamlined, universally agreed-upon metrics.

We don’t need hundreds of duplicative measures. A small set of high-yield, clinically meaningful standards — like PROMIS Physical Function and Pain Interference for musculoskeletal care — could anchor quality measurement across programs.

2. Focus on what matters to patients.

Instead of checking boxes on process measures, we should prioritize high-yield, clinically relevant outcomes: improved function, reduced pain, speed of recovery, return to work, and patient satisfaction.

3. Avoid survey fatigue.

Demonstrating quality shouldn’t require endless forms. By using a handful of validated questionnaires, delivered at the right intervals and in patient-friendly formats, we can get richer, more actionable data without overburdening patients or staff.

4. Simplify reporting through shared infrastructure.

Rather than forcing every practice to build its own bespoke systems, we need centralized clearinghouses and registries that standardize submission and automate compliance. This reduces waste and levels the playing field for smaller practices.

5. Leverage technology to reduce manual work.

AI and automation can transform quality measurement from a burden into a byproduct of care:

Natural language processing to pull outcomes directly from clinical notes.

Predictive analytics to identify patients at risk of complications and intervene early.

Conversational AI to collect PROMS via text or voice, instead of long paper forms.

Automated audit prep, eliminating thousands of wasted staff hours.

6. Provide real-time feedback loops.

Instead of waiting years for CMS reconciliations, clinicians should see immediate, transparent dashboards showing their performance against benchmarks. Done right, this can be motivating, not punitive.

7. Prune ineffective measures.

Every quality program should have a sunset clause. If a measure doesn’t drive better care, retire it. Otherwise, we’ll drown in metrics that measure everything but improve nothing.

Quality is More than Compliance

At Commons, we want to move past quality as a compliance exercise. Our goal is to build an elegant, transparent, tech-enabled, and scalable framework that rewards delivering consistently better outcomes for patients. Demonstrating quality should be a differentiator and source of pride, not a paperwork burden.

Healthcare won’t be transformed by adding more acronyms. It will be transformed when we measure fewer things, measure them better, and use those measures to fuel continuous improvement. More than ensuring compliance, quality should be the foundation of value creation.

If we want healthcare to truly compete on value, quality has to look less like bureaucracy and more like innovation.

Excellent analysis on the burden of quality measures in healthcare. This aligns with my previously published thoughts (https://www.pcplens.com/p/the-quality-of-quality-measurement).

The problem with measuring quality is that the metrics don't represent good care at a practice level. This is especially true for small practices, as their "sample patients may not represent the population." Penalizing independent practices then leads to consolidation and worse care overall.

Furthermore, often "poor quality" is also a representative of SDOH (e.g., uncontrolled BP, diabetes, or rehospitalizations) as people may not afford medications, healthier food, or live in a highly stressful environment.

We focus on process measures, as outcomes are hard to measure. However, poor outcomes are more often due to structural issues than bad processes. This is the reason why our zip code is a better predictor of mortality.